Upcycling refers to the use of “skins, seeds and cellulose components of plants that consumers don’t want to eat.”

It’s an ancient and universal practice. Probably the most widespread is the use of these by-products as animal feed.

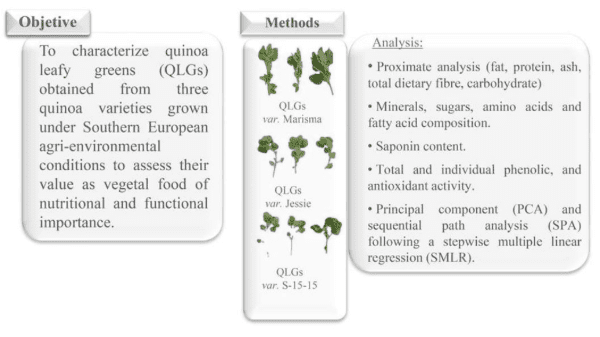

It isn’t often that these discarded materials can be incorporated directly into food for humans. It is still less common that they can be turned into fresh produce. But this may be the case with quinoa greens.

Many people are familiar with quinoa, whose seeds are used as a kind of grain; it is rapidly becoming incorporated into mainstream diets. (My acupuncturist tells me that it is extremely rich in magnesium, if that is of any use to you.)

But has anyone heard of eating quinoa greens?

It’s a possibility. In fact, quinoa greens turn out to be very nutritious. A new scientific study concludes: “A protein content higher than 35 g 100 g-1 dw with a well-balanced essential amino acid composition was found making them a good source of vegetable protein. In addition, elevated contents of dietary fibre and minerals, higher than those detected in quinoa seeds and other leafy vegetables, were found.”

Another finding: “Quinoa leafy greens (onwards QLGs), which consist of young leaves with or without petioles or shoots, can be consumed raw (in a salad), stir-fried, stewed, or steamed being an example of promising foods with a high nutritional and functional value. . . . They contain high quantities of protein, with all the amino acids necessary for humans, and low quantities of reducing sugars, carbohydrates, and fats. Furthermore, QLGs also contain high levels of potassium (K), manganese (Mn), and copper (Cu), and moderate levels of calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), sodium (Na), and zinc (Zn).”

The background to this research has to do with the need to find new food sources for a human population that is expected to reach 10 billion by the midcentury. The issue is more complex than many think: in a developed country like the United States, mere quantity of calories is not the concern: many Americans eat far more calories than they need.

But some developing nations have not yet managed to produce or acquire even enough basic calories to feed their people.

“These countries tend to be concerned about having enough staple foods in the markets and accessible to their citizens,” comments C. Peter Timmer, a Harvard emeritus professor who is an authority on agriculture and rural development.

“That emphasis, however,” Timmer continues, “is being increasingly challenged by the international nutrition community, now with considerable support inside FAO [the UN Food and Agriculture Organization], which wants the focus to be broadened to a ‘healthy diet,’ with more attention to micronutrients, vitamins, fiber, and diversity. The produce sector obviously plays a key role here. The big policy debate is over the cost of a healthy diet compared with an energy-sufficient diet.”

As a result, quinoa greens, now seen merely as a by-product, might be brought into the diets of poorer nations.

In this country, it’s easy to see how quinoa greens can fit into the broad portfolio of leafy greens, appealing initially to food sophisticates and those concerned with nutrition, and possibly entering the mainstream just as quinoa seeds have.