Chestnut Market Summary

Image: Natali Zakharova/Shutterstock.com

Chestnut Market Overview

Chestnuts have been enjoyed for centuries. Asian chestnuts (Castanea crenata or C. mollissima) are mentioned in poetry as far back as 5,000 years ago and early Europeans arriving in the New World found forests of American chestnuts (Castanea sp.) blanketed the East Coast from Georgia to Maine and as far west as the Mississippi River.

But while the Asian cultivars are still going strong, the American chestnut was wiped out in the early 1900s. An attempt to import Chinese chestnut trees brought in chestnut blight, to which Asian chestnut trees were mostly immune but American trees were not.

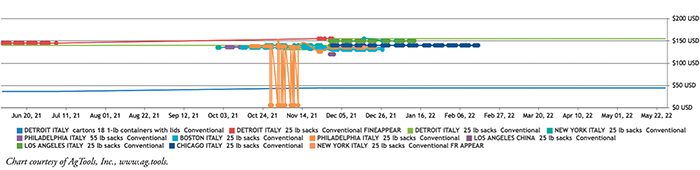

Fifty years and up to 5 billion dead trees later, the American chestnut began to recover. Producing less than 1 percent of the world’s chestnut supply, most chestnuts consumed in the United States come from Italy.

New varieties, developed at the end of the twentieth century, include a wheat gene resistant to chestnut blight that produces a tree almost identical to the wild American chestnut.

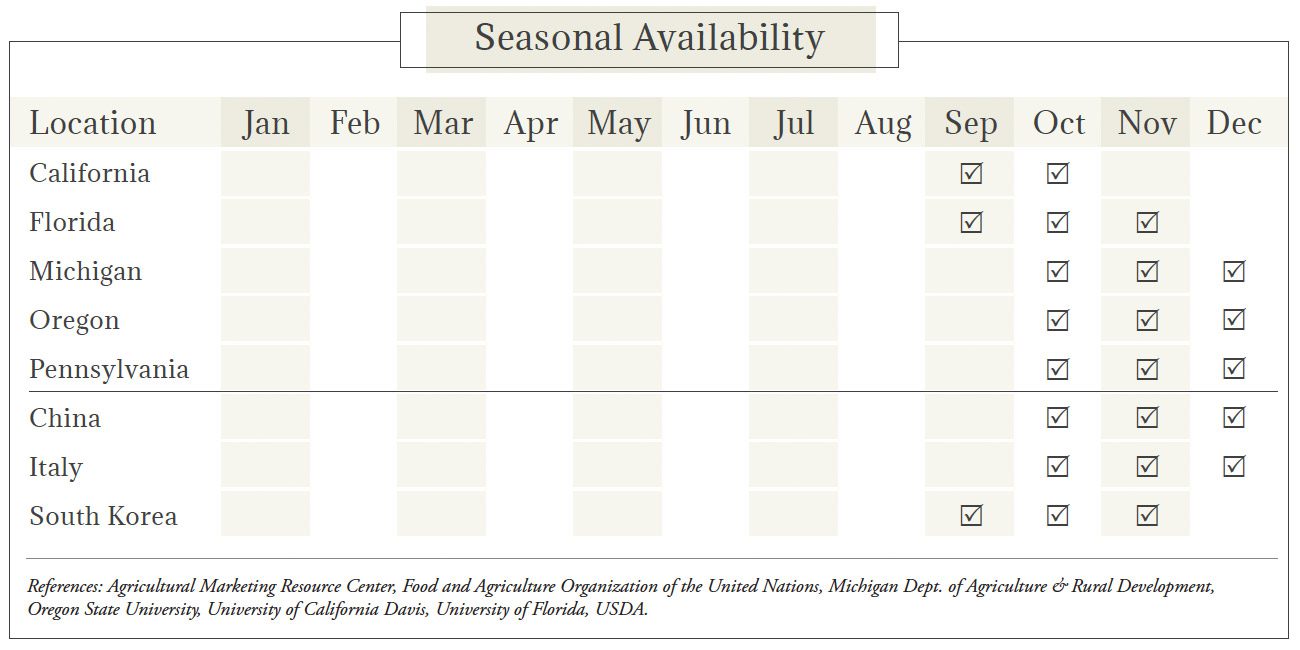

Harvest and marketing occurs from October to December in most growing regions. Chestnuts can be roasted, eaten raw, or ground into ?our for baking. Larger nuts are preferable for fresh market sale, which are sold in the shell and classified by size (large, giant, jumbo, or mammoth) by the USDA.

Types & Varieties of Chestnuts

There are four major species of chestnut tree. The American chestnut has an upright tree form and produces smaller, sweeter nuts. The European chestnut is native to Western Asia, Europe, and North America. European trees also have an upright form, but tend to produce bitter or bland nuts that are larger though harder to peel. Both American and European trees are susceptible to blight.Chinese chestnuts are native to Northern and Western China and tend to have a low, spreading form with many branches at ground level, though some Chinese cultivars have an upright form. Trees yield medium-sized, sweeter, easy to peel nuts.

Japanese chestnuts are native to Japan and China, are also blight-resistant, and tend to be smaller with a spreading form. Nuts from Japanese trees are large but have an undesirable taste, so trees are used primarily for hybridization.

Cultivation of Chestnuts

Chestnut trees thrive in warm, temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Although they can tolerate a variety of environments and climates, a long, warm growing season and mild winters are ideal. Deep, well-drained soil with a 5 to 6.5 pH level is best.

Depending on the species and cultivar, trees will grow as tall as 100 feet. Most trees are propagated via grafting and budding.

Drip irrigation is recommended both to establish an orchard, provide an easy means of fertilization, and prevent weeds and unwanted growth between rows.

Pollination is via wind with some assistance from insects; cross-pollination is necessary as chestnut trees are self-sterile.

New growth appears on branch tips where sunlight hits the tree, so pruning should maximize exposure. Open-center trees let sunlight into the middle, top, and sides of the tree branches. Trees grown from seedlings begin to bear nuts in 3 to 5 years.

Grafted trees bear after 2 to 4 years. Burrs should be removed during the initial years to allow trees to grow and mature. Fully mature trees can produce between 1,000 and 1,500 pounds per acre each year.

Chestnuts are encased in a sea urchin-like, spiny burr that contains the large hard nuts. Nuts develop and fill out in the last 2 or 3 weeks before ripening. Burrs either split open to release nuts as they ripen or fall to the ground with nuts enclosed.

Hand- or mechanical harvesting can be used for upright-form trees; spreading trees must be hand-harvested as shaking does not adequately knock nuts from drooping branches. Fallen nuts decay quickly and may dry out or become sunburned, so nuts should be gathered frequently. Some growers install catch frames or mesh netting to prevent nuts from hitting the ground. Any remaining burrs should be removed from trees after harvest.

Chestnuts are primarily sold fresh in the shell and classified by size (large, giant, jumbo, or mammoth) by the USDA.

Quality indicators are size; uniform shell color and gloss; plump kernels; bruise, crack, sprout, and decay-free nuts; peelability; sweetness; and lack of off-flavors.

Pests & Diseases Affecting Chestnuts

Chestnut trees are susceptible to a few pests such as the chestnut weevil, oriental chestnut gall wasp, spider mites, shot hole borers, filbert worms, and even deer and squirrels.Diseases of concern include the aforementioned chestnut blight, as well as alternaria, aspergillus, botrytis, fusarium, penicillium, phomopsis, phytophthora root rot (also known as ink disease), leaf spot, powdery mildew, and oak root fungus. Asian chestnuts are particularly susceptible to twig canker.

Storage & Packing of Chestnuts

Once collected, nuts are removed from burrs and immediately cooled, washed, sorted by size, and stored at 30 to 32°F in breathable mesh bags to prevent decay.For burrs that have not yet opened, either a few days of ripening time or exposure to ethylene speeds up the process with no effect on nuts. Exposure to carbon dioxide for 5 to 7 days followed by cold storage will help prevent mold, sprouting, and deterioration.

Chestnuts can last several months when stored, but will dry out even at high humidity levels (85 to 95%), so protective packaging is needed. Nuts are high in starch and low in fat, more like potatoes or apples than other tree nuts.

References: Cornell University, Purdue University, University of California Agricultural & Natural Resources, University of Florida/IFAS Extension, University of Illinois Extension, USDA, Western Growers Association.